Ghosting: Escaping the Uncomfortable

We ghost anytime we want to escape the uncomfortable.

“He came to my house one night, and I pretended I wasn’t there,” 36-year-old Jenny Mollen disclosed her story in a New York Times article, in which she ignored a man she had been seeing, saying it was because of an incident in her family. While there was an incident…it was months prior. According to Mollen, “If you disappear completely, you never have to deal with knowing that someone is mad at you and being the bad guy.”

Welcome to our culture of ghosting: the act of suddenly cutting off all communication with an individual, without any explanation. It is an escape from the uncomfortable–the ultimate silent treatment.

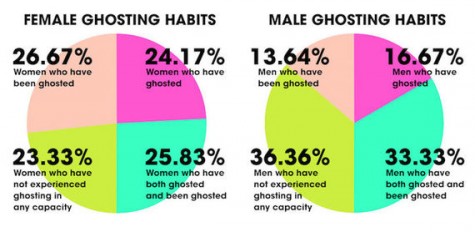

Whether it is a friend or a significant other, anyone is susceptible to receiving the short end of this stick. While in the past this behavior would have been seen in only the most apathetic of people, it seems that this apathy has been growing as the years have gone by. A 2015 Huffington Post poll found that 26% of women, and 33% of males have both ghosted and been ghosted.

Results from an Elle.com survey of 120 women and 65 men. A majority have experienced ghosting in some fashion.

As Maya Borgueta, doctor of psychology at GoLantern.com, states in her 2015 article, “ghosting is about wanting to avoid confrontation, avoid difficult conversations, and avoid hurting someone’s feelings.” Ultimately, we ghost because we think it will protect others’ feelings, yet that couldn’t be further from the truth.

When we make the choice to ghost an uncomfortable situation, we are undoubtedly choosing to be selfish. We are only thinking about alleviating our own troubles, without any consideration for how the other person might feel as a result. This is not only beyond disrespectful, but can also be extremely distressing to the recipient.

“I believe that [the person] would feel hurt, emotionally and mentally,” says senior Luis Segura.

He’s not wrong.

A 2015 Psychology Today article finds that the act instills in the receiver the sense that they did something wrong, damaging their self-esteem, without any ability to question what the original problem was, which is the biggest detriment to ghosting.

A 2012 study published in the Journal of Research in Personality finds that avoiding/withdrawing from another person is one of the worst ways to handle a difficult situation. It leaves problems unresolved, and misunderstood; in the end, nothing gets done.

Unfortunately, this goes far beyond the realm of interpersonal relationships. In its most basic form of escaping the uncomfortable, ghosting is almost everywhere. How many times have we avoided an event we were invited to, instead of letting someone know we simply didn’t want to go? How many times have we avoided uncomfortable talks that involve racism or sexism out of fear that someone might get hurt? These things are uncomfortable, but they cannot be ghosted.

AVHS Psychology teacher Jennifer Heineman sheds some light on our tendencies to avoid the uncomfortable. “How many people now say, when you’re going to Thanksgiving, ‘as long as you don’t talk about politics?’” According to her, one of the main reasons that our nation is becoming so polarized is because of the fact that, due to not wanting to offend others, we avoid uncomfortable conversations. In essence, we don’t want to speak our minds if it means that someone might get hurt.

Even if we do find ourselves in the middle of a difficult situation, she explains that we still find other ways to ghost. Terms like “awkward” and “my bad” are really just cop outs that lack depth or sincerity. They give us the opportunity to not have to deal with the issue at hand.

Heineman explains that ghosting is something that we all do. “We disavow the notion that [difficult conversations] should persist, but really, it’s just making them harder.” She notes that this happens in our families, where uncomfortable topics–such as sexual education and unresolved emotional/mental tensions–are quickly shied away from. It happens in our schools, where conversations about race are held off because of the belief that we don’t know enough to give our two cents. It happens just about anywhere ghosting can be used as a method to escape discomfort.

Fortunately, there is hope. If ghosting is all about wanting to avoid the terrible uneasiness in the pit of our stomachs, we have to embrace that feeling. Because it is that uneasiness that is telling us that something is wrong, or that something must be said. In the end, we have to get comfortable with the uncomfortable.

“You have to allow for the notion that, maybe, you don’t know everything you think you know,” says Heineman. “Even if you don’t know what you’re doing, even if it makes you terribly uncomfortable, you still talk about it.”

It’s as simple as that. If we want to move forward in our relationships, our families, our classrooms, or even our nation, we have to allow ourselves to look past our own discomfort. In the face of the uncomfortable, when we have to decide between ghosting or fighting…I say we fight.