A Cycle of Industry Cover-Ups

Granulated sugar is poured in Philadelphia, Monday, Sept. 12, 2016. A new study released Monday details how the sugar industry worked to downplay emerging science linking sugar and heart disease.

Exposed.

After 50 years, nutrition scholar Marion Nestle of New York University uncovered the not so sweet truth about the real effects of sugar. Back in September, shocking research surfaced in JAMA Internal Medicine about an age old cover up of scientific evidence regarding sugar’s contribution to heart disease.

A sugar industry trade group was found to have paid three Harvard scientists nearly $50,000 in the 1950’s (the equivalent of $500,000 in today’s world) as compensation to direct research surrounding heart disease away from sugar and place the focus on dietary fats.

The year-long work that Nestle piloted led to many more findings of corporation-funded research.

“Is it really true that food companies deliberately set out to manipulate research in their favor?” wrote Nestle in her “Food Industry Funding of Nutrition Research” publication. “Yes, it is, and the practice still continues.”

The fact is, this was not the only time scientific research was funded by food industry giants. In 2015, The New York Times found Coca-Cola to be funding research that led to an ad campaign urging consumers to add more exercise into their lifestyle instead of cutting back on calorie intake. In June, the Associated Press uncovered how a candy trade association funded research that revealed children who eat candy tend to weigh less than children who don’t.

Nestle’s discovery of food corporation funding has left some in the medical field less than pleased about the cover up.

“If false data is taught and we inform our patients with it, what does that say about me as a professional?” asked Kellie Parmett a registered nurse at the Dakota County Correctional Facility. “And more importantly, what does that mean for my patients?”

“Health is not black and white,” continued Parmett. “You could see one doctor and they could tell you one thing, and another doctor might tell you something different.”

When it comes to the general public, how do they know what to trust and what to only take at face value?

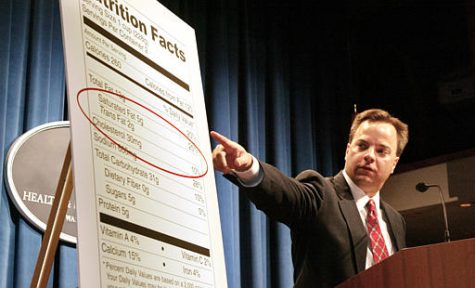

“Nowadays, it takes scientific research to read a basic food label,” said Parmett. “You can’t always trust what’s in the fine print.”

It is clear that this issue is not isolated only to those in the medical field. This circulation of false research is even strongly regarded by some students within the AVHS community.

“I think it’s terrible that scientists in charge of our food aren’t being objective and unbiased,” said junior Emily Westcot. “Then we don’t know what we are putting into our bodies, and the thought of that is frightening.”

Senior Calvin Hill had a more personal connection to the issue. “It’s disturbing,” he said. “As a Type-I diabetic, paying attention to the nutrition in food is a very big deal. The fact that I might not be able to trust the labels is scary.”

This leaves many to wonder if there is a solution to this problem. It all goes back to Nestle’s recent publication. The more people continue to fight for accurate information in regards to health and nutrition, the more change that will happen.

For now, it seems everyone’s safest bet is to stick with their gut. If a study seems a little off, look into it. When in doubt, check where the money is coming from and be conscious of food-industry manipulation.

Sierra Knudsen • Oct 19, 2016 at 10:09 am

I’m interested in what kind of repercussions the trade group and the scientists could face? Coco Cola did this too and I didn’t even hear about it. I think it says a lot about what society values when its not common knowledge that major brand companies are skewing studies for profits. How susceptible are our scientists to bribery? It’s scary how money can affect people who we put a lot of trust into.

Maggie Sammon • Oct 19, 2016 at 9:07 am

I find it really sad that now days it’s hard to find foods that are actually healthy for you.

Caitlyn "Madame Espelho" Glass • Oct 17, 2016 at 3:36 pm

Scientists in charge of our food are wasting time not telling about what’s really we’re digesting, especially in food. There are times I feel like I don’t even trust the labels. We also can’t tell the good and bad because of this cover-up.