A Billion Dollar Question

How Much Should We Be Giving Up For Our Sports Stadiums?

U.S. Bank Stadium came in at a cost of $1.1 billion. The Vikings opened their 2016 season in the stadium back in September.

Last summer, the Minnesota Vikings opened the doors to their brand new stadium in downtown Minneapolis at an estimated $1.1 billion price tag, according to the Star Tribune. Standing on the site of the old Metrodome, the stadium was built with the promise of revitalizing the downtown area and giving Vikings fans a one-of-a-kind experience.

U.S. Bank Stadium is just the most recent billion-dollar stadium to be built within the past ten years. According to USA Today, the Vikings’ new home joins AT&T Stadium, Levi’s Stadium, MetLife Stadium, and Mercedes-Benz Stadium as the only arenas in the NFL to cost over a billion dollars.

When huge stadiums like these are proposed to city and state officials, the big question that they will ask first is how the stadium will be funded; nowadays, most are funded by a joint investment from the team owners, the city, and the state. According to the Star Tribune, the city of Minneapolis contributed $150 million, and the state of Minnesota paid $348 million; most of that money is coming directly from taxpayers.

However, the use of public money for sports stadiums is an extremely controversial topic, and for good reason. The public does not own professional sports teams, and they certainly don’t get a sniff of the money that they make off of tickets, merchandise, and other items. So why do we spend our tax dollars on billion dollar stadiums instead of roads, education, and so on?

Team owners for years have been able to get public funding through a few tactics. One of those tactics is the promise of redevelopment and economic growth around the stadium.

Little Caesars Arena, the new home of the Detroit Red Wings. The arena is the centerpiece of a $1.2 billion redevelopment project in downtown Detroit.

Take a look at Detroit’s brand new $627 million arena, Little Caesars Arena. The arena, the future home of the Detroit Red Wings, is the centerpiece of a $1.2 billion redevelopment project called District Detroit, according to the project’s website. Red Wings owner Mike Ilitch, who also owns the Little Caesars Pizza chain, has a net worth of over $5.8 billion dollars, according to Forbes. Yet, the city has agreed to pay half of the cost of the arena. What makes this even worse is that the city approved the funding plan for the project nearly a week after the city declared bankruptcy, according to CNN.

There’s also not much evidence to suggest that building the arena will boost the economy in any way. In an article with Stanford University News, economist Roger Noll, an expert in the economics of sports, and has found that stadiums “do not generate significant local economic growth, and the incremental tax revenue is not sufficient to cover any significant financial contribution by the city.” Noll went on to say that teams should pay for their own stadiums, saying that “most teams are owned by wealthy individuals who could pay for their own.”

The promise of redevelopment around the stadium is not the only tactic teams use to get public funds. Another reason they give is the possibility of hosting the Super Bowl.

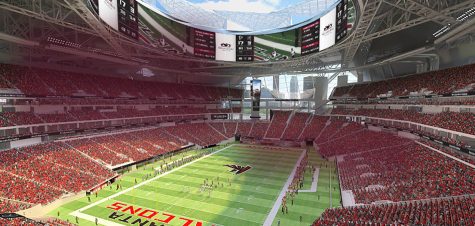

A prime example of this is the Atlanta Falcons’ new Mercedes-Benz Stadium. One of the main reasons why funding for the project was passed was to attract a Super Bowl to Atlanta, which they accomplished by winning the bid for Super Bowl LIII.

The Super Bowl has always been perceived by cities and the general public as a way for a city to benefit from hundreds of millions of dollars of revenue towards small businesses. However, this is a highly disputed fact by many economists and government officials.

Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta was mainly built to try to attract the Super Bowl to the city.

In an interview with CNBC, P.J. Johnston, an NFL spokesperson for Super Bowl 50, said that the economic impact estimates for Super Bowl 50 “have varied widely from a couple hundred million to nearly $800 million.” When you add the cost of building the stadium and the highly unpredictable economic outcome of hosting the Super Bowl, the cost of building the stadium and preparing the city for the big game could outweigh any possible benefit.

Mercedes-Benz Stadium cost over $1.6 billion, and taxpayers will be paying around $320 million for it, according to the stadium’s website. With the possibility of not being able to turn as large of a profit as projected, there’s a good chance that building a brand new stadium for a Super Bowl may not be worth the cost.

One of the final reasons team owners are able to get their stadiums publicly funded is the threat of leaving for another city. For nearly twenty years, NFL teams have been blackmailing their cities with this message: help us build a stadium or we’re moving to Los Angeles.

The San Diego Chargers, Oakland Raiders, Jacksonville Jaguars, Buffalo Bills, Tampa Bay Buccaneers and Minnesota Vikings have all threatened to relocate to Los Angeles if they didn’t get a new stadium, according to FOX Los Angeles. All of these teams were able to stay in their cities, but the Vikings were the only team to get their stadium.

Los Angeles Rams owner Stan Kroenke is privately funding a $2.6 billion stadium in Inglewood. It is the most expensive stadium in the world.

The St. Louis Rams, however, pulled the trigger on the relocation-to-Los-Angeles threat. While there was a lot of public outcry and an opportunity to build a new stadium in St. Louis left on the table, according to ESPN, team owner Stan Kroenke moved the team anyway.

What makes the Rams’ relocation to Los Angeles different is that they weren’t attracted to the city by the chance to use public funds; Kroenke was actually planning to build a privately funded stadium. The Los Angeles Times reports that the stadium in Inglewood will be the world’s most expensive, with a price tag of over $2.6 billion, and it will nearly all be funded by Kroenke. This means that taxpayers won’t have to pay a cent.

While relocation is always a controversial topic, the way that the Los Angeles stadium is being funded is how new stadiums should be funded. The owners should be responsible for paying for the stadium – not the taxpayer.

Think about it. The teams are the ones gaining the profit from ticket sales, merchandise, concessions, and most other events in the stadium. We could invest $400 million into a stadium, and the chances are that we wouldn’t get back what we put into the project.

There is no substantial evidence that these projects economically benefit the area, and even when events such as the Super Bowl are hosted, the potential income that companies make in the local area is highly volatile and not guaranteed to help pay off the debts on a stadium.

U.S. Bank Stadium is definitely not a bad thing for the state to have. It’s already regarded as one of the best stadiums in the world, and the Vikings will have a great place to play for many years.

This does not, however, take away from the fact that we as a state paid over $400 million for a football stadium that most of the population won’t use.

Whether it was worth it will remain to be seen.

Further Reading:

Sports Stadiums Don’t Generate Significant Local Economic Growth:

http://news.stanford.edu/2015/07/30/stadium-economics-noll-073015/

More information on U.S. Bank Stadium:

http://www.startribune.com/go-inside-u-s-bank-stadium-the-new-star-of-the-north/377165911/

LastWeekTonight story on sports stadiums:

Shawn Switzer • Oct 19, 2016 at 9:07 am

Super good article! It was interesting hearing how teams get the stadium that they want by using blackmail. I hope to go see the new stadium soon!

Angela Dabu • Oct 19, 2016 at 9:01 am

Great article! I’ve been to the stadium and it’s nice!

Alison • Oct 17, 2016 at 8:03 pm

Well written Jack.