Cyborgs Among Us

How we use technology to improve our bodies

A close up of Kylie Maxfield’s contact lenses- can you see them?

When my sister Haven stumbles out of bed most mornings, the first thing she does is head to the bathroom to pop in her contact lenses. Immediately, her vision improves–she can see details clearly. Many mornings my sister joins the ranks of people known as augmented humans: people who use technology to alter and improve their bodies.

Human augmentation is a rapidly growing reality in our lives. Instead of technology being separate from us, it works with our biological environment. But how exactly do we use technology to improve our biology? As technology rapidly becomes more advanced, what does the future of augmentation look like? Is it ethical to alter our bodies with rapidly expanding technology? How far can we go–and how far should we go–to modify our bodies?

Augmentation is all around us–in our families, on the streets and even within the hallways of our school. Apple Valley High School students are no exception to human augmentation. Many people, like my sister, wear contact lenses- a form of simple augmentation.

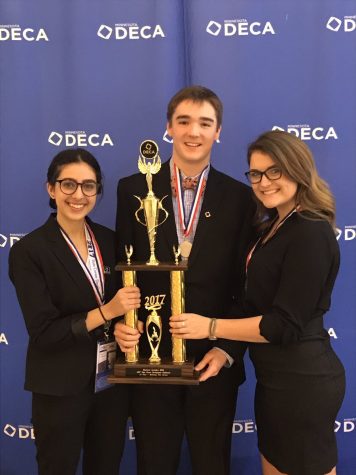

Two AVHS students proudly repping their contact lenses! (Left to Right: Elise Jensen, Kylie Maxfield)

Senior Reid Jarvi is an example of using technology as part of biology in a more complicated way–he wears a hearing aid in his right ear. Describing the function of the hearing aid, he says, “It’s essentially a microphone that amplifies sound without giving any depth perception. I’m able to hear things at higher and more intense levels.” Jarvi lives day-to-day weaving technology and biology–he is a more common example of how mechanical technology works with the body.

Most of the examples of augmentation we see are for medical purposes. Senior Sarah Grambo, 2016 informative speaking champion, spent several months last year researching the topic of human augmentation for her speech. She describes this phenomenon saying, “Anything that’s outside the skin is the easiest and most accessible way to monitor or improve health.” In some cases, people may even go as far as calling people with augmentations cyborgs.

But wait! Isn’t a cyborg just something out of science fiction movies? I’m pretty sure I saw a cyborg on Teen Titans, and I don’t see anybody like that walking around the streets. Maybe not yet. But the future of human augmentation is here and rapidly becoming more common.

Senior Reid Jarvi’s hearing aid- technology working with biology!

The dictionary definition of a cyborg is “a person whose physiological functioning is aided by or dependent upon a mechanical or electronic device.” That is happening today!

One familiar example of cyborg technology is prosthetics. In fact, one company called Braingate is currently researching mind-controlled prosthetics. Sound far-fetched? It’s not. In fact, it’s already happened. A New York Times article titled “How Science Can Build a Better You” describes the case of Cathy Hutchison. Devices called electrodes are implanted into her brain, connected to a computer, and then connected to her prosthetic arm. With this, she can move her arm and even lift a cup of coffee to her mouth–just with thought!

A more extreme case of a cyborg is Neil Harbisson, who had an antennae attached to his skull by surgery, helping him distinguish colors through the frequency of their vibrations. In a Newsweek interview article with Harbisson called “Part Human, Part Machine,” he talks about the idea of a cyborg: “For me, a cyborg is someone who feels their technology is a part of their biology.”

These examples may be extreme, but they’re not uncommon. Technology improves around us daily and the ways we improve our bodies with it continues to move from science fiction to reality.

But as we push the limits of biology mingling with technology, the ethics of human augmentation become a discussion. The question may be not how far can we go to improve our bodies, but how far should we go?

Sarah Grambo discusses her ideas about the future of biotechnology and ethics. “I think augmentation is going below the skin for more medical applications. The concept of having a machine in your body raises some ethical concerns.”

Apple Valley physics teacher Mr. Laurent shares some concerns on the matter. He talks about the practice of pre-screening children: “You can know so much about an individual before they are even born now.” In terms of using technology to define us, Laurent says, “We don’t look at each other as people anymore. You lose the humanness of people.”

The ethics of human augmentation are a minefield of opinions and concerns. Several ethical questions spring up with the minefield: What does it mean to be human? Should we replace good for better just because we can? Should we accept our flaws? Should healthy people be allowed to participate in dramatic augmentations?

John Donoghue, Brown neuroscientist and Braingate team leader, has a strong opinion: he doesn’t allow people who aren’t impaired to have access to his prosthetic technology. He represents those who think augmentation shouldn’t be used to better already fully functioning bodies.

Bioethicist Thomas H. Murray takes another approach, discussing the possibility of a super-attention pill: “It might actually be immoral for a surgeon not to take a drug that was safe and steadied his hand. That would be like using a scalpel that wasn’t sterile.” Murray suggests that using augmentation to better society is a practical and even praiseworthy practice.

As the future of human augmentation becomes our reality, we may all be faced with the question: how far would you go to modify your body?