Stepping up after a (Short) Fall: Addressing Budgetary Gaps in Minnesota State Education Spending

Part One: Insufficient Funding, the History, and Impact

By: Tai Henrichs

“The stability of a republican form of government depending mainly upon the intelligence of the people, it is the duty of the legislature to establish a general and uniform system of public schools.” These words from Article XIII, Section I of the Minnesota constitution underscore the value of education. High-quality education provides people the tools to understand the world around them, making it vital to the guidance of a democratic government. It is thus highly concerning if the education system is failing its students.

During the spring of 2018, Democratic Governor Mark Dayton was locked in a political clash with the Republican-controlled legislature over education spending (Hinrichs). Dayton had proposed that the budget provide $138 million in additional funds to provide relief to schools that would face budget deficits for the 2018-2019 school year. The legislature proposed an alternative budget that would add $225 million for education. $50 million would have could from fees owed to schools by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources while the remainder $225 would have been provided by loosening restrictions on existing funds previously limited to use for staff development and community education. Dayton vetoed that proposal. The result is that sixty public school districts across Minnesota are currently faced with budget deficits (Golden). Altogether, districts faced $127 million in deficits for the 2018-2019 school year.

Those districts have responded in a number of ways to their budget shortfalls. The Star Tribune reports that the Robbinsdale district cut 70 staff members, half of which were teachers, to respond to a $10.6 million deficit (Golden). The district also increased its cap on class sizes, further increasing the workload of the newly shrunken staff. In addition to staff cuts, many districts such as Forest Lake have continued the long-standing practice of covering education expenses through referendums that propose to levy higher local taxes for education funding. Finally, some, such as the Rosemount-Apple Valley-Eagan district I attend high school in, have covered costs using reserve funds, though this is only sustainable as long as reserve funds are not fully drained.

These changes are not without consequence. That much grew more apparent during an interview I conducted with a high school teacher in the Rochester school district who had directly felt the impact of staff cuts (Sagstuen). They work in a high school English-Language-Learner (ELL) program, and this year, the number of teachers for the program had been cut. Previously, they had already been teaching about twenty-four students per class, which is already quite large for an ELL class. Following staff cuts, their class grew to forty students, making it more difficult to engage directly with students and build the relationships that can be of particular importance when supporting students who less familiar with American customs and education. An article authored by William J. Mathis, a director of the National Education Policy Center at the University of Colorado Boulder, details the litany of benefits studies have found to accrue with smaller classes:

[…] college attendance, graduation rate, student engagement, persistence, and self-esteem is reported as higher. The gains in test scores are attributed to the greater individualization of instruction, better classroom control and, thus, better climate. Teachers have more time for individual interactions with children, consulting with parents, and giving greater attention to grading papers. (6)

Although the exact magnitude may vary widely across schools, the impact is clear; it will not be unusual for students to suffer if budget deficits go perpetually unaddressed.

-

Source:

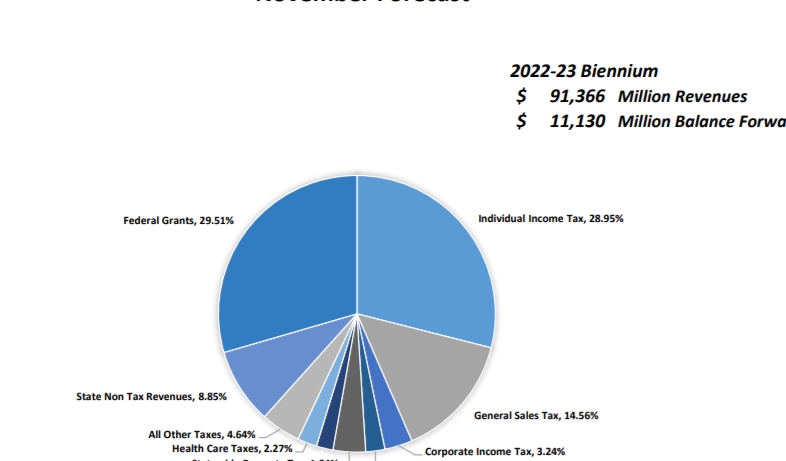

Minnesota Management and Budget -

Source: Minnesota Management and Budget

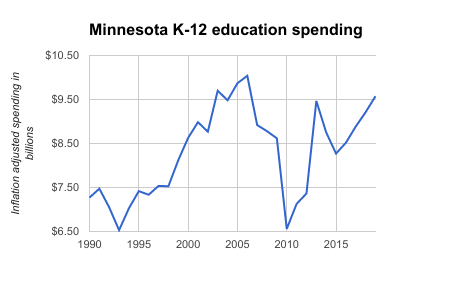

Despite the above average severity of the funding gap this year, it is nothing unusual in Minnesota’s history. Education budgets were last implemented in 2015 and 2017. During both of those years, many schools’ expenses exceeded what they would receive from the state and federal government, which caused sixty full-time staff cuts just in the Twin Cities area in 2017 (Magan, “Minnesota schools are getting $483M”). One reason for its annual prominence is that K-12 education is the largest item in the Minnesota state budget, accounting for forty-two percent of the budget with the next largest area, healthcare, accounting for about twenty-five percent (Kaul). These costs will likely need to grow further in the future. For one, inflation-adjusted education funding has just recently recovered to levels comparable to before the Great Recession, which began in 2008. The effects were not immediately apparent, but from 2007 until 2010, education funding decreased from 8.92 billion dollars to 6.56 billion dollars. The first budget to provide comparable amounts of funding to the pre-recession 2007 budget was in 2017, which included 8.89 billion dollars of funding (Magan, “Minnesota schools are getting $483M”). If this was the only reason motivating proposals for increased funding, it would seem that, by now, everything has been about corrected for, yet the damage wrought by the Great Recession has been compounded by increases in enrollment that have accompanied growing special education and ELL programs (Magan, “Do Minnesota schools need more money or reforms?”).

Special education funding, in particular, faces an unusual dilemma. Minnesota funding for education can be broken into separate parts. The way allocations are designed to work, school districts receive a general education budget that is meant to cover the educational needs of students without the need for special education. This is based on two elements. The first is called the “basic education formula”, which allocates resources based on the number of students in a district (Kaul). The second is an aggregation of miscellaneous other needs such as coverage for ELL programs, extracurricular activities, and extra transportation funding for rural schools. The portion of the budget designed to cover special education funding is meant to be covered by additional funds, though it is typically covered by the same funding bill. Besides these state-level funds, forty percent of special education costs are supposed to be covered through the Title I program, which is federally operated; however, federal funding levels have never breached eighteen percent in Minnesota, which has created a long-standing funding gap that must is often compensated by local school districts (Schneidawind). In 2016, the federal funding gap in special education for Minnesota was $679 million, which districts covered by allocating that amount of their general education budget towards special education. This cross-allocation from their general budgets means that the overall budgetary process becomes skewed as now the funds provided are now insufficient for the general population as measured by the legislature’s own funding equations. Until Minnesota can successfully pressure the federal government to meet its mandate, it will need to compensate for at least a portion of the current gap. Thankfully, no one has proposed cutting special education funding during funding debates in the state government the past few years, but it is clear that the problem of insufficient funding for both general and special education will persist if nothing is done to combat them. Possible reforms and budgetary adjustments will be described in the second part of this article, to be published n week.

Sources available here: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1I9UVG33wZLjysfpGzrTgNzYk88xhgJ8LB-03X1k0hWI/edit?usp=sharing